Whole Grain Wheat: DIY Flour Yields Transcendent Bread

An excerpt from Unprocessed: My City-Dwelling Year of Reclaiming Real Food

Finally, my minimill arrives in the mail. It’s a heavy, narrow device, smaller than a wine bottle, bigger than a ruler. I mount it on the edge of my coffee table, the only counter in my apartment with a lip wide enough to support the two-inch base. I wind the flat-top screw snug to the wood and give the rectangular metal canister a shake to make sure it’s snug. It extends only six or seven inches above the coffee table; the housing that will hold the whole berries before they crowd into the grinder is smaller than a fist.

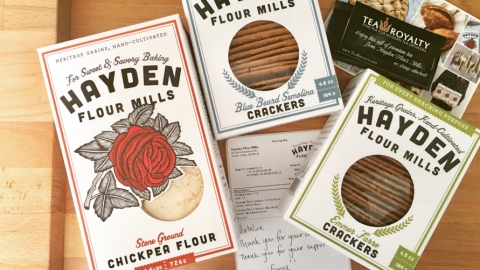

Although I now have a sack of Jeff’s (Editor’s note: Jeff Zimmerman from Hayden Flour Mills) freshly ground flour in my kitchen cabinet, any lingering doubts and morning-after regret that may have surfaced when I woke up on Monday and remembered I’d bought a hand-operated grain mill dissolved on Tuesday when I opened my weekly e-newsletter from the Tucson CSA. Along with okra and corn, green beans and chilies, for the first time since I joined the CSA we will also receive a half pound of Paloma White Winter Wheat berries harvested at Crooked Sky Farms, just south of Phoenix. Clearly the world wants me to mill wheat.

But not yet. The mill is mounted and I crouch before it, ready to grind, until I realize that I forgot to wash my berries. Reluctantly, I accept that washing my wheat—rinsing off the bits of straw and dirt that were carried in from the field—is a necessary step, so I pour the baggy into a mesh sieve and stick it under the faucet. I spread the berries across the baking sheet to dry and call my parents, as I do most Sundays. . . .

Twenty minutes later, when I hang up the phone, water continues to cling in the berries’ crevices. I remember farmer Kyle telling me that one of the biggest costs of industrial wheat production is the energy required to run the drying machines that keep a 20-story granary at 14% humidity, so I wander into my bathroom and grab my hair dryer. Five minutes with a Revlon Ionic Ceramic and the berries are ready to rumble. Corralled into a cup, poured into the mill’s housing; I press the crank, unconvinced that anything’s going to happen. It’s not going to move—this won’t work. Sixty dollars will not buy me the ability to mill wheat in my own home—I am already planning my e-mail to Kyle, to the Victorio company. But then the crank shifts forward, the berries dive inward, and out of the milling cone spills a fine dust of speckled beige flour. Flour! I keep grinding and the flour keeps spilling, melting from the turning crank of the milling cone. Flour, whole from a berry; flour, whole from a field.

As I watch the wheat berries crowd together over the slowly rotating mill, as I grind the crank and the wheat tumbles out the other end, transformed into the soft Spackle of flour, the process becomes so much less mysterious. Stalk to berry to flour, soil to seed to energy: I get it, just a little bit, how it was that someone ever imagined food from the earth.

It takes seven or eight minutes of continual motion to crank through two cups of wheat berries, and by the end, my right bicep burns. I kneel over my coffee table and run my fingers through the bowl of flecked flour. It’s warm, surprisingly so. It’s not hot, not burning, but certainly warmer than the air. (Warm like 110°?) And so I don’t wait; I bake bread. I bake bread now, with my warm flour. Yeast dissolves, oil whisks, honey floats in swarmy bubbles and my freshly ground whole wheat crumbles and dissolves into a humid mess. Two cups of wheat berries produce four cups of flour, but my recipe calls for six, so I pull from the cabinet the bag of Sonora wheat flour that Jeff gave me.

Kyle’s bitter words echo in my mind, so I lick my pointer finger and stick it in to the bag and then lick the fine dust that sticks to my skin. It tastes like . . . nothing, really. It textures more than tastes, smooth like chalk dust as I rub it around my tongue. I grab another taste, and this time it tastes sort of mineral-sweet. I grab the bag of Trader Joe’s Whole Wheat Flour, the same flour that formed my first loaf of bread, and remove the clothespin clasping it shut. I’ve never, before this moment, tasted raw flour before, but in goes my finger and out goes my tongue. It’s gritter than the Sonora wheat. It’s gritty and bitter. I squish the flour between my tongue and the top of my mouth and the granules release a stream of sour flavor. I cannot believe that I’ve never noticed this before—I cannot help but roll my eyes at this bag of flour, so unequivocally earning its own demise.

Again I bake bread. Throughout the day, the dough rises and falls with my kneading. It rises, falls, rises and then arranges itself into loaves of dough. “The word dough comes from an Indo-European root that meant ‘to form, to build,’ and that also gave us the words figure, fiction and paradise (a walled garden),” writes Harold McGee in On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. “This derivation suggests the importance to early peoples of the dough’s malleability, its clay-like capacity to be shaped by the human hand.”

My human hands shape this hybrid bread, built of the grains of the Sonora wheat and the flecks of my little grain mill, still perched on my coffee table.

Forty minutes later my hybrid loaf of heirloom wheat and fresh flour doesn’t emerge from the oven as high as I expect. It’s a roomy bread, sprawled across the baking sheet. But, as one must do when confronted with bread fresh from the oven, I slice off a broad slab from one end. It requires no honey, asks for no butter. I grab the opposing crusts and watch as the dough stretches apart between the two sides, the air bubbles popped apart by warm yeast now yawning open, expanding wide, until finally they split.

The bread rolls through my mouth with yeast-wheat-honey warmth as I chew through its fibers. It’s so much better than my first loaf, both because my baking skills have improved and because I can feel the flakes of wheat rubbing through my mouth, because I can imagine them whole.

I could eat the whole loaf. The smell is everywhere, in my hair, my throat, on my clothes. But this particular loaf of bread doesn’t trigger me. I want to eat more, but I don’t want the stomachache, don’t want the rush of insulin as my body wrestles with its starches. Instead, I slice it up. I slice it up, put it away and on Monday morning, when I am dashing out the door to work, I toss a tomato between two slabs and slather on some goat cheese. Six hours later, the inside of the bread has gone soggy, but the outside crust continues to crunch, sweet like oranges, dense like nuts. It’s a carby lunch, this thick bread. It’s a fatty one, too, this rich cheese. But it fills me up, satisfies me, and although it takes less than 10 minutes to consume, the memory of it lingers throughout the afternoon, sticks to the inside of my stomach and the back of my tongue.