Cooking with Frances: The Incredible Edible Desert

As the daughter of a U.S. diplomat, I’ve been lucky enough to live all over the world, and I’ve eaten just about every local food you can think of—from ants to zebra. But when I moved to Tucson, I was stumped.

All I could see around me was cactus: pretty purple cactus, scary spiny cactus, small cactus, tall cactus, skinny cactus and fat cactus … lots and lots of cactus. How on earth could someone survive here? What could they possibly find to eat? Since I never go more than five minutes before planning my next meal, I was really curious (in fact, obsessed), about the traditional foods of this region, especially the foods of the local people.

My quest to learn more led me to Tohono O’odham Community Action (TOCA), a small nonprofit on the O’odham Nation. This remarkable organization introduced me to Frances Manuel, a tribal elder with a vast knowledge of traditional O’odham foods. Thus began my hands-on culinary immersion in how to find, pick, cook and preserve the fascinating wild and cultivated desert foods of the Sonoran Desert.

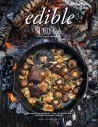

Frances and I didn’t cook things that most people have ever heard of—much less eaten. Our menus included javelina jerky, cholla cactus buds, saguaro syrup, mesquite juice, yucca flowers and tepary beans. Foods that have sustained the Tohono O’odham people for centuries.

Each week for several years, until her death in December at 94, I made the drive from my home in Tucson to Frances’ home in the beautiful tiny village of San Pedro, surrounded by mountains and groves of saguaro cactus. As I turned off busy Route 86 onto the winding, scenic road to San Pedro, I could feel a calmness and an anticipation wash over me. I so looked forward to my cooking days with Frances—the warmth of her cozy kitchen, her welcoming smile and her simple lovely home.

She welcomed me wholeheartedly as a friend and colleague, always with a smile and a joke or two. How she loved to tell stories and jokes. And boy, could she cook. Frances never had a “secret” recipe, she gladly shared everything with me and with whomever was interested in learning about the fascinating desert foods she had grown up preparing and eating with her grandparents.

Frances also had great patience. Never one to measure, she gamely tolerated my running after her, notebook and measuring cups in hand, to find out just how much flour she used in her famous empanadas or how many cups of water she added to her delicious white tepary bean stew. She pronounced Tohono O’odham words over and over, encouraging me to repeat them with her as I struggled to stuff a microphone under her flowery dress to capture her special songs and stories.

She knew everyone: She was sure that Junior would help me find wild spinach, that Jose would help me whittle sticks for roasting corn, that Florence would make saguaro jam with us, that Jake would bring over some usabi, that Jimmy would get me javelina jerky. And they did.

Frances taught me that the desert is really a garden, full of delicious healthy foods if you only know what to look for. Early spring brings delicate opon (lacy) spinach also known as poverty weed; Easter time is for picking ciolim (cholla buds) before they blossom on the spiny Buckhorn cholla cactus plant; ripe magenta saguaro fruit is gathered in late June and turned into a deeply flavored, smoky syrup. Farmers plant bawi (tepary beans), ha:l (O’odham squash), keli ba:so (old man’s chest) melons and hu:n (60-day corn) in the ak:chin (floodwater plain) fields to be watered by the monsoon rains. Late summer and fall harvests yield ha:l mamad (baby squash), I’ibhai (prickly pear fruit), cuhuggia (amaranth greens) and ripe wihog (mesquite pods).

Never again will I look out at the desert and see only cactus. Frances opened my eyes to the incredible wealth of the desert and I still hear her voice full of laughter and wisdom and feel her looking over my shoulder as I cook, encouraging me to go on.