Farming on Asphalt with Nature and Technology

"Fish poop?" I ask, incredulously.

"Fish poop," Mark Rhine says, rather matter-of-factly.

I'm standing in a parking lot just north of downtown Chandler, overlooking a blacktop that's been converted from rows of parking spaces into an extraordinary, self-contained ecosystem to grow organic, nutrient-dense food. Rhine and Marlo Ibanez, the owners of two-year-old RhibaFarms, have just explained their aquaponics farming system and now they're giving me the grand tour.

I've boiled down to two words the engineering marvel of this recirculating food system that uses less water than a backyard swimming pool. Clearly an oversimplification, but it's something I can wrap my head around.

Aquaponics is the convergence of hydroponics (growing food in water) with aquaculture (fish farming). That's where the fish waste comes in–and goes out, more accurately.

Through a series of tanks, pipes, pumps and troughs, RhibaFarms' delicious vegetables are fed by 11,000 gallons of effluent water from a school of tilapia fish, and the plants return the favor by cleaning and filtering the water before giving it back.

Growing food in water populated with fish is not a new form of farming. It has been done for thousands of years in China, the Middle East and Mesoamerica, but it's not everyday you stumble upon an aquaponic farm smack dab in the middle of a bustling city, much less in a parking lot.

A good place to start is with a question: Why? Why aquaponics? Why on a parking lot?

High Tech Meets Ancient Ingenuity

Rewind about 10 years ago. Rhine and Ibanez had just left a cable TV company to form their own broadband company. Ibanez's background is in engineering, and Rhine is well versed in construction and, it seems, sales and marketing.

Over the next 10 years, the business partners grew the company into multiple broadband companies across four states. The high-stress, fast-paced technology industry eventually took a toll on their mental and physical health. They were miserable. So they sold the broadband companies.

In an effort to return to a healthy lifestyle, Rhine began incorporating wheatgrass into his diet. When he couldn't find a local source, he decided to grow his own. At the same time, he realized a business opportunity: He could become a major source for wheatgrass for the entire Valley. He convinced Ibanez to build a greenhouse and RhibaFarms was born.

Researching farming techniques, the guys stumbled upon aquaponic farming. Fascinated by the prospect of a natural and sustainable system that required no farmland and precious little water, the partners jetted off to Hawaii–twice–to attend aquaponic farm school.

Something's Fishy

They then converted their Chandler-based broadband company headquarters into a giant greenhouse. Inside the building are offices, a commercial kitchen for preparing the produce for sale, and a temperature- and humidity-controlled nursery where seeds are germinated. Outside, the back parking lot is divided into a wet side and a dry side.

The wet side is covered with several low-to-the-ground water troughs. On this warm, sunny spring day, a sea of lettuce is bobbing gently in tiny pots, buoyed by Styrofoam planks. I can hear water gurgling in the pipes that run between the troughs.

If I close my eyes, it's not hard to visualize a babbling brook. But then I open them and see asphalt, Styrofoam and pipes. And beautiful multi-colored lettuce leaves.

The troughs are in the middle of a multi-part system that begins with a chest-high, boxy fish-rearing tank under a shelter next to the two-story building. Underneath the aerated Styrofoam cover is where the tilapia splish, splash and do what they were brought to RhibaFarms to do: create organic fertilizer.

It's feeding time and I get to do the honors. Ibanez removes the cover and Rhine hands me a cupful of organic fish food pellets. I see a thin, black nylon net covering the surface of the water but I don't see any fish.

"Sprinkle it on top," Rhine says, "then you'll see them."

I shake a few pellets on top and before I can pull my hand back, I fully get the purpose of the mesh netting. Hundreds of tilapia attack the surface with a shockingly violent explosion, splashing water everywhere in their frenzied feeding.

I pour in the rest of the food–from a slightly higher elevation–and watch with awe as the surface turns into a ferocious, bubbling cauldron of fins and tails. As quickly as the mayhem began, it ends. Every last pellet has been devoured and the fish retreat to the depths of the tank. The surface eerily returns to a benign pool of gentle waves.

The Details

Water from the fish-rearing tank flows into a smaller tank called a solid settler tank. The heaviest fish waste sinks to the bottom, evacuated later for soil fertilizer.

The remaining water travels into another tank where microbes begin to convert the remaining fish waste into ammonia and nitrites and finally into nitrates: a dissolved form of nitrogen that plants can absorb as nutrients.

The nitrate-laden water passes through a de-gassing tank before it's released into the growing beds. The plants absorb the growth-giving nitrates–in essence, filtering the water.

At the end of the system, a sump tank pumps the clean, plant-filtered water back to the fish tank. Water loss results only from mild evaporation and plant aspiration.

"It's a completely natural, totally organic system," Rhine says. "We're vested in keeping our fish healthy naturally–we don't use any pesticides or herbicides–and we're growing healthy produce because we've got healthy fish who provide organic nutrients."

Staying Dry

Originally the plan was to grow wheatgrass in the aquaponic system but it turns out that wheatgrass doesn't grow well in water, which is why the other half of the parking-lot-turned-farm is called the dry side.

Rows of shelves under shade screens are stocked with flats of wheatgrass and RhibaFarms' other main crop: micro greens in the form of shoots–pea, sunflower, broccoli and radish, among others. There are basil, parsley and other herbs, too.

Crops are seeded by hand in organic coconut coir (shredded coconut husks) and germinated in the indoor nursery before moving outside to finish growing under the unrelenting Arizona sun.

Farming on an asphalt island has its challenges. RhibaFarms is not quite three years old, and Rhine and Ibanez admit there have been plenty of ups and downs. Even so, both seem to embrace the challenges with high spirits and certainly healthier bodies.

Ibanez says he dropped 60 pounds just from the physical activities required to run the farm, but he still hasn't developed a taste for wheatgrass.

"We took a left turn from our technology path because we got fed up with the stress and we realized where our food comes from is far more important," Rhine says.

"Our goal is to grow nutrient-dense food," he says. "We haven't figured it all out yet. We grow great food but Mother Nature is a tough one. And we're trying to pull this system off in a parking lot."

I chime in: "With fish poop."

"Yeah," he says, "with fish poop."

Chicken Town USA

Soon after purchasing the Ranch House land, Ibanez constructed a large chicken coop Rhine dubbed "Chicken Town USA."

A 100-strong flock of American Heritage chickens are currently providing fertilizer for the garden plots and eggs for sale.

They're working on an adopt-a-chicken program, too. For a weekly fee, they'll take care of feeding and boarding your tagged bird, and in return you get the eggs.

Where to find RhibaFarms Produce

Most of the wheatgrass RhibaFarms grows is sold to a distributor. The wheatgrass ends up in Whole Foods, juice bars and health stores; most of the produce is sold directly to caterers and chefs.

For direct consumer sales, RhibaFarms operates a booth at the downtown Phoenix Public Market (phoenixpublicmarket.com) on Saturdays, where they sell wheatgrass, sprouts, greens, vegetables and eggs. Their sprouts are also available indoors at the market's Urban Grocery and Wine Bar.

Meanwhile, Back at the Ranch

Rhine and Ibanez have additional farming plans in the works, this time in the dirt. Earlier this year, they purchased "the Ranch House," a three-acre plot located on a county island near Gilbert.

The Ranch House site has been designed with the same meticulous engineering finesse they used for the Chandler aquaponic system.

They're experimenting with a one-way aquaculture system at the Ranch House, installing catfish and bluegill tank systems to water the fields.

Rhine and Ibanez are developing a CSA program to partially fund the soil-based farm, and have already planted beans, potatoes, melons and squash among other vegetables. Check the RhibaFarms website for updates.

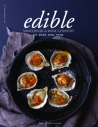

Photos courtesy of RhibaFarms