VISIT: Spend a Day at St. Anthony's Greek Orthodox Monastery

How many times have I heard from both desert dwellers and tourists that there is nothing noteworthy to see, smell or eat between Metro Phoenix and Metro Tucson?

Well, that may appear to be true if you never veer off Interstate 10, but there is a wealth of culinary and cultural wonders hidden in Pinal County halfway between Arizona's two largest cities. A number of those surprises come from an enclave of Greeks who make some of the best olive oil, artisanal bread and stuffed grape leaves I have ever tasted.

It is not merely their way of preparing food that excites me, but the care with which these Greek immigrants grow this food in an arid landscape that others might dismiss as inherently unproductive. While their call to a contemplative and prayerful life is the core reason that six Greek Orthodox monks of St. Anthony's Monastery came to this desert in 1995, they have also excelled in producing fruits, vegetables, pistachio nuts and olive oil in this land of little rain.

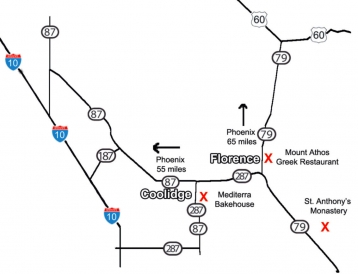

What's more, they have attracted to Pinal County a number of other Greek Orthodox devotees whose family businesses now enrich the lives of Arizonans as well. Along with a pilgrimage to chapels, gardens, gift shop and acres of orchards and vineyards at St. Anthony's south of Florence, you may want to consider a day-long culinary tour of the county by adding on visits to the Mount Athos Restaurant and Cafe in Florence and the superb Mediterra Bakery in nearby Coolidge.

First, a word about arriving at St. Anthony's in the proper state of mind and appropriate attire. While the monks and their abbot do indeed welcome visits to see their gardens and orchards and to purchase their food products and live fruit tree saplings, St. Anthony's is first and foremost a spiritual sanctuary and is simply not suited to the boisterous tourist or inquisitive foodie. The monks are cordial and generous in orienting visitors to the lush gardens, orchards and vineyards, but they insist that both men and women be conservatively dressed, reserved in their behavior and restricted to certain pathways through the gardens. The day visitor's guide posted on their website outlines the proper code of conduct and the strict dress code, as well as the current hours of permissible visitation (typically 10:30am to 2:30pm seven days a week, but check for closures on holidays).

That said, the monastery is well worth visiting, not only because of its beauty, but because it reminds us how important contemplative traditions have been to the development of cultures and cuisines of desert oases all around the world. The monks not only grow most of what they eat, but also contribute extraordinarily fine food products to other communities through their relationship with Dan and Diego Rosado, the founders of the Local Natural Foods distribution network.

The monastery is easy to get to from either Phoenix or Tucson by getting on the Pinal Pioneer Parkway (Highway 79). After crossing miles of creosote bush flats and saguaro cactus forests, it is a rather stunning surprise to come upon a true oasis rising up from the desert floor, replete with date palms, olive orchards, vineyards and vegetable gardens. Twenty-four acres of farmlands, ornamental gardens and fountains surround beautifully constructed chapels, cathedrals, dormitories, guest houses and the trapeza dining hall. As soon as a guest arrives, he or she is offered a cup of water and the confection known as loukoumia (Greek or Turkish delight) made with fruit juices, nuts, gelatin and powdered sugar. After checking in at the gift shop for a brief orientation by a monk and a wardrobe adjustment if needed, visitors are free to follow the designated trails on their own through all the greenery.

Nevertheless, many visitors linger in the gift shop for a moment longer, looking at all the hand-crafted foods prepared by the monks and their desert neighbors. The tall glass bottles of unfiltered olive oil first caught my eye, for they virtually glow with golden hues when a sunbeam reaches them. But there is a kiosk stacked with jars of honey and citrus marmalades, mango chutneys and hot pepper sauces, baklava pastries and koulourakia cookies, which one may purchase and take home.

The monks offer bags of dried herbs of exquisite quality, including some of the most aromatic rosemary, oregano, basil and sage I have ever come upon. The searing sun of the Sonoran Desert has surely heightened the intensity of fragrances concentrated in these herbs.

As I came out of my orientation at the gift shop, Father Mark signaled me over and offered a freshly bagged gift of Greek sage tea, a mixture of sun-dried desert herbs. He also sold me a vigorous 18-inch-tall fig sapling, which produces pale greenish fruits. Then he directed me to the orchards and gardens while I placed my newly purchased fig tree in the shade.

After meditating in the Byzantine-style chapel for a while, I followed the designated trail past the numerous date palms out toward a series of vegetable gardens that were producing an abundance of produce greater than that I have ever seen from French-intensive beds placed in the desert. Netted or screened to reduce bird damage and to offer partial shade, the monks have developed such fertile soils for these gardens that they produce massive watermelons, squashes, cucumbers, and tomatoes on drip irrigation alone. Despite the intense heat, they also grow artichokes, asparagus, spearmint, basil, green beans and many kinds of chile peppers in these shaded gardens because of the moisture-holding capacity and tilth they have nurtured in the soil.

Gazing out beyond the gardens, you see acre after acre of citrus, pistachio and olive groves. The monks grow four kinds of olives, including the most ancient variety in the Sonoran Desert, the Mission olive, which is celebrated on the Slow Food Ark of Taste for its flavor and antiquity in Arizona and California. In addition, they grow the Manzanilla de Sevilla and Kalamon varieties, the latter which has begun to offer harvestable quantities of Kalamata olives, a rarity in desert climes. In late September and October, when the monks are cold-pressing the first run of olives into an unfiltered oil that they sell, it is possible to request a guided visit to the press and sample the freshest, and mostly deeply flavored, oil I have ever tasted.

As I left St. Anthony's, I couldn't help but be amazed at the curious juxtapositions: recent Greek immigrants conserving the oldest variety of olive to grow in North America; and saguaro cacti towering among date palms and the belfry of St. George's chapel. This is the way the desert itself wakes us up and keeps us alert: Sometimes what at first appears to be a mirage is a true oasis of life.

After purchasing some baklava at St. Anthony's, I had a craving for Greek food for lunch so that the monks' pastries could serve as my dessert. Fortunately, the Mount Athos Restaurant and Cafe just eight miles north of the monastery on Highway 79 in downtown Florence has a menu with ample options for those who love Greek food. When I mentioned to the waitress that I was trying to decide between a Greek salad and the dolmadakia plate of stuffed grape leaves with rice, she noted that the salad came with grape leaves, so that I did not have to choose between the two. I make stuffed grape leaves regularly in the warak inab style of the Lebanese, but must admit that the Mount Athos Greek version were among the most flavorful I have tasted in some time. I cannot vouch for their pasticio, mousakka or roasted leg of lamb, but Mount Athos is well worth a return visit in order to sample their other fare.

My final stop for the day was in the heart of nearby downtown Coolidge, Arizona, a former farming hub that has been hit hard by Arizona's economic strife. And yet, along Main Street there is the most wonderful bakery that has graced Arizona in years, the Mediterra Bakehouse. Opened in 2012 by Nick Ambeliotis, a Greek baker from Pittsburgh who had already honed his shaping of artisanal breads into a fine art form over the previous five years, the bake house had eight exquisite kinds of loaves available the day I arrived, including a paisano, a ciabatta and Mount Athos Fire Bread, with its dark crisp crust. Ambeliotis has received national recognition for reviving the tradition of mass bakings of an ethnic Easter bread, tsoureki, with volunteer parishioners from Greek Orthodox churches in Pennsylvania.

At Nick's second location, in Florence, associate baker Antonio Campana exudes the same enthusiasm for handmade, long-fermented breads. The artisanal breads of Mediterra Bakehouse are now sold at four farmers' markets in Metro Phoenix and at Whole Foods and will soon be available in other locations. The bakery's kitchen is in open view of the counter, so you can see four or five bakers working at their craft during your visit.

These experiences reminded me of how much faith-based communities contribute to the food diversity of our state, a fact that most Arizonans recognize only when they frequent the many church-sponsored food vendors at ethnic food festivals like Tucson Meet Yourself. That growing and sharing food are considered sacred rituals by many should not be lost on us. Eating itself is a sacred act, one through which we may either celebrate creation or, when done carelessly, damage the very world that nurtures us.