Rooted in Traditional Ways

The Seeds

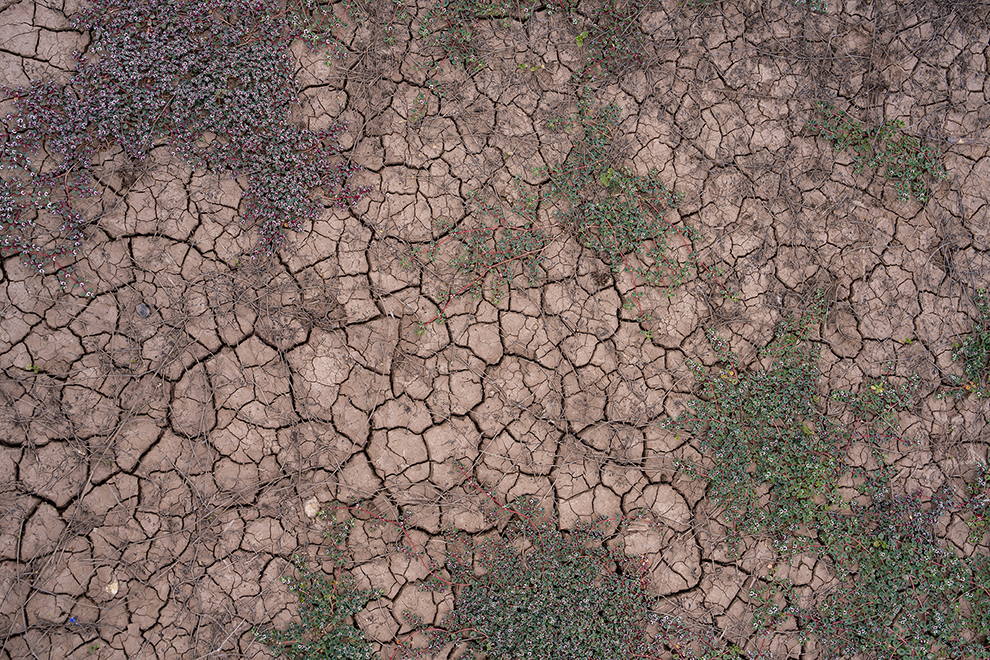

Amson Collins parked his white pickup truck adorned with the official seal of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community (SRPMIC) next to the roughly one-acre field on a brisk, overcast morning in March. It rained lightly as Collins explained that the field was tilled last year, mulched during winter and cover crops were planted to enrich the soil. Now in spring, a group of community members set rows and dug shallow holes with saguaro spines to prepare for planting squash, corn, tepary beans and more.

“A lot of people come out here and look at this field and they’re, like, ‘How do you guys grow anything in this? It doesn’t look like it’s good soil,’” he said. “Well, this is the original dirt. It’s different for us over here with our seeds.”

Collins, 37, was born and raised in Salt River, located to the east of the Phoenix metropolitan area, where the O’odham have farmed for thousands of years.

His great-grandfather was a farmer who passed down heirloom seeds to his daughter,

who gave them to her son, who in turn passed them on to Collins. Traditionally, families preserved seeds to be planted and cared for by subsequent generations in this fashion. Although the practice is not as common anymore, Collins is trying to change that.

Collins works as a community garden technician for the Cultural Resources Department (CRD) of the SRPMIC government. That morning in March, workers hired as part of a day labor program were planting a field, adjacent to the community garden, that belongs to the department. When harvested, the food will be distributed to other community members and help replenish a seed bank.

From a young age, Collins said, he developed an interest in the land by learning from his dad and elders to identify wild plants and to hunt game. His interest in O’odham tradition and history has taught him the importance of their seeds.

“All these seeds, these plants are super drought tolerant,” Collins said. “They don’t need a whole lot of water. They’re durable. They’re tough. They’re adaptive. They’ve been here for a few thousand years. They’ve always been farmed here. And the big secret key, though, is the river water.”

The Rivers

Salt River is one of several communities in Arizona of the O’odham and Piipaash, also known as the Pima and Maricopa, names introduced by European arrivals; the tribes refer to themselves by the former.

More specifically, the community is Onk Akimel O’odham, or “Salt River People,” who are closely related to other O’odham groups, and Xalychidom Piipaash, or “Upriver People,” who are part of a broader Piipaash. The two distinct tribes have long farmed along the Gila and Salt Rivers and enjoyed a close relationship.

Beginning in the 1840s, tens of thousands of people traveled across Arizona en route to California during the Mexican-American War and the subsequent California gold rush. Later, gold discoveries throughout Arizona brought more settlements to the territory. The O’odham and Piipaash played an integral role in assisting travelers and the U.S. military with food and protection, growing and selling more than one million pounds of excess wheat in 1862 alone.

By the 1870s, river systems were greatly disrupted as non-Native people settled into what is now Phoenix. The Swilling Irrigation Canal System diverted water from the Salt River to raise and sell crops to a growing population. It was among the first efforts to utilize a system of irrigation canals stretching hundreds of miles, built from around 300 to 1450 CE by the Hohokam, earlier cultures from whom the O’odham descend. Today, much of Phoenix’s canal system still follows the groundwork created by the Hohokam.

As disruptions to the river’s natural flow made farming difficult, the O’odham and Piipaash faced severe food shortages and soon became reliant on commodity foods from the U.S. government. Decades later, a network of dams and reservoirs supplied water to Salt River and the Gila River Indian Community (GRIC), partially restoring farming practices, but by then their way of life had been irrevocably altered.

Still, many traditional practices continue through formal institutions like the Cultural Resources Department and informally within families, communities, and by individuals like Collins, who helps oversee maintenance of the field.

Collins said many people in the day labor program are struggling to get on their feet while dealing with addiction, violence and mental health, which are larger issues within the community.

“That is all a result of generational trauma that goes all the way back from when the Gila River got dammed up,” Collins said, “[It] forced our people to not be able to farm.” Relying on commodity foods, he added, brought diabetes and chronic illness to the community.

He also noted that when farming stopped, most traditional foods and their seeds—which grow brittle over time when not replaced—were lost. He estimates that what they have today represents only a small percentage of the diverse foods traditionally cultivated.

In the field, the team plants a variety of heirloom seeds known in O’odham as ha:l (squash), huñ (60-day corn), and bav (tepary beans), that will be irrigated by the river.

“The river water that comes through is like a natural liquid compost tea of fish fertilizers, fish emulsions, plant breakdown . . .” Collins said. “All those nutrients are in that river.”

Beyond the river, in the near distance, a number of mountain ranges were visible that Collins shared the O’odham names for, such as Gakodk and S-veg Do’ag, also known as The Superstitions and Red Mountain.

The Lands

Stetson Mendoza, 43, is the community garden coordinator for the Cultural Resources Department. Prior to his involvement here, he helped develop a similar community garden in Lehi on the border of the SRPMIC. Before that, he planted corn and tepary beans in Sacaton with his father.

Although he hasn’t always been involved in farming and is still learning, he mentioned he has learned the importance of proper spacing for different plants and how to harvest them correctly.

“We forgot who we were,” Mendoza said, “and a lot of people don’t know because [when] we were all kids, it wasn’t taught to us, our traditional ways. I hate to say that, but that’s what happened and we kind of lost a lot of our culture.”

Mendoza gestured to an adjacent area with a vatto, or ramada, where he’d like to build an olas ki, or round house where anyone can come visit. He hopes it will provide more opportunities for a younger generation to learn how O’odham and Piipaash traditionally lived and to spend more time outdoors.

These projects are part of a larger plan to develop programs that will complement one another, said Kelly Washington, director of the Cultural Resources Department.

Washington originally became involved with the language program, which works to preserve and provide instruction for O’odham and Piipaash languages, nearly 30 years ago. The language program and other cultural programs were consolidated into the Cultural Resources Department in 2005 and Washington has served as the director since its inception.

Currently, an old day school built in the 1930s is under renovation and will serve as a new Cultural Resources Department building. It will contain classrooms for language instruction and a kitchen where the community can learn how to preserve and cook traditional foods from the community garden and field.

Washington said they’d like to promote their Native calendar more. For the O’odham, June represents the New Year when Jujkida, or the rain ceremonies take place to welcome the monsoon rains and baidaj, or saguaro fruit, are harvested.

Like Collins, he sees a clear link between changes in diet away from traditional foods and the prevalence of health issues within the community, which the department programs look to resolve. In addition to addressing health issues, he said, being outside, planting crops and cooking together is “just good for the soul.”

“We’re connected to the desert, we’re connected to the river, we’re connected to all these cycles,” Washington said. “We’ve lived here for thousands of years, so our bodies are in sync with all of that. And with the changes we’ve seen in the last century or so, we’ve kind of gotten out of sync and it hasn’t been good in a lot of ways.”

The department employees and other members of the community who helped plant the field will harvest the food in summer during the O’odham New Year and Jujkida celebrations. The seeds will be preserved and used in years following, when they hope even more people will participate and learn about the O’odham himdag, their way of life.

Special thank you to Daniel Swanson, Tohono O’odham, for help with this story.

Learn more about the Salt River Pima Maricopa Indian Community: www.srpmic-nsn.gov