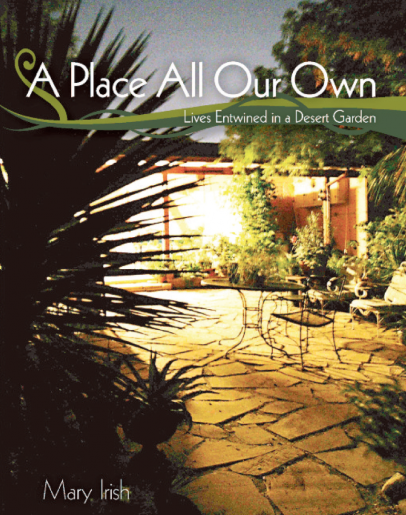

A Place All Our Own by Mary Irish

A Place All Our Own: Lives Entwined in a Desert Garden

by Mary F. Irish (©2012 The Arizona Board of Regents)

Building a garden is no different than building a life; often the pieces and parts come together without much conscious effort, creating a recognizable pattern only when you look back on it. A garden in which you live for a long time, just like a life of almost any length, develops around choices little and big, conscious or not: the placement of a path, or a wall, or a plant, sometimes selected with a particular result in mind but just as often a stumbling response to changing circumstances. After a while all the choices you make in a garden run together and a pattern emerges; one day you look around and are stunned to see that the garden has a well-defined look, an ambience that marks it as your own.

This is a story about how that happened for me and my husband, Gary, in a garden in the desert city of Scottsdale, Arizona. We did not set out to make such a garden. We simply grow plants the way some people bake cookies – we just gotta do it. But this garden, in this place, taught us a lot, not only about the desert and how it works but also about ways to garden in such a unique and frequently daunting place. It is also a tale about shared lives, human and otherwise, and the inestimable value of living as close to all the other lives as you can.

The book is not intended as a manual for designing a garden or growing desert plants. It is a chronicle, a personal recollection of what it took to get this garden this far. While it is an idiosyncratic and personal story, I hope that our experiences and trials prove helpful. Whether what we did works for you or not, we wish all gardeners the best garden they can create.

People who tend a piece of land, whether expansive like a farm or minute like a patio home, are forced to deal relentlessly with other living things and with the immense variety of twists and turns resulting from their march through the garden. More often than not other lives, invited or not, become the agent of choice and change in the garden. Choosing one style of fencing may be dictated by the need to keep marauders out of the plants, which then leads to the rearrangement of an entire section of the garden. Or an adjustment made to accommodate pets or the preferred nest sites of well-loved birds nearly always runs counter to our own interest in pruning, allowing a plant to grow larger or more prominent than we first intended.

Good design principles and their application can help launch a garden. We find such dictums handy for ordering our thoughts and controlling some of our most ridiculous desires – but for us, good design alone won't make a comfortable garden. Over the years we have come to a humble acknowledgment that a lot, if not most, of the life of the garden is well outside our control, and that it will be best if we let it evolve out of the life we and others live in it. It is our firm belief that a garden allowed to form its own pattern from our whimsical choices and heartfelt desires, so that it gets its true pulse from all the lives that enter and live in it together, is the best garden there is. A truly comfortable garden is one where all the lives with whom we share it become intertwined, a place where most lives are tolerated, indeed welcome, and where a moderate live-and-let-live approach is enough to settle our differences.

Every gardener knows that you don't build a garden all by yourself, just as you don't build a life or a career or a skill all by yourself. You bring a lot of yourself to it – your experience, talents, interests, and imagination – but numerous teachers, friends, stolen ideas, and captured images lurk in the corners of every life and garden. All of these other lives embed themselves in our daily activities and become integral to our gardens and, like a lot of family members, some of these other lives present great challenges. Some companions offer more than you give in return, while others are greedy and take away too much. But in the end, we cannot escape the knowledge that they all had a part in creating the garden we have and the life we cherish.

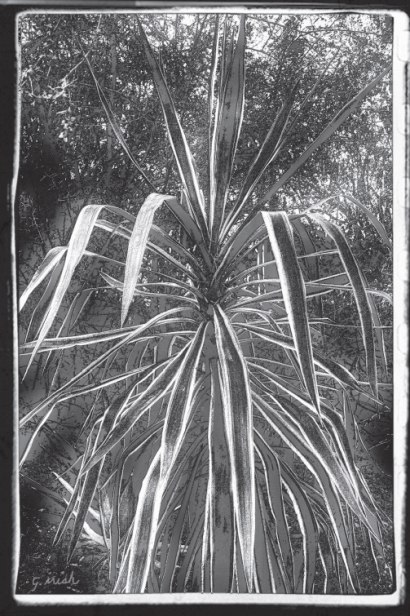

This garden has been our laboratory and our refuge, our greatest accomplishment and our most exhaustive endeavor, one that we have shared with a vast array of others, all of whom have intertwined themselves into our garden and our hearts. It has consoled us in troubled times, allowed us to wallow in self-congratulation when things have gone well, provided us with the opportunity to lazily watch cactus wrens attend to their daily chores, allowed us to marvel at the flowers of oxblood lily (Rhodophiala bifida) as they rise up like sparklers each fall, and soothed us with the elegant grace of a palo blanco (Acacia willardiana) during the brutal summer heat. All of these lives bring us joy and delight; joy in the bounty of a garden and its connection to a wide range of desert lives, and delight in having done something well, in having accomplished something – even if it is just getting the watering done.

We took our time coming out to Arizona, dropping off plants in East Texas and dogs in Amarillo, camping in the mountains above Santa Fe until finally diving down into the desert in mid-June. As we came over Gonzales Pass and looked out over the breadth of the immense Salt River Valley, waves of heat rose up from the desert's floor, crushing our small, poorly air-conditioned car under the full weight of 107-degree heat. We could hardly believe it. We had both grown up where it was hot, plenty hot, and in my case without the benefit of air-conditioning, but this was altogether different. It was our first introduction to the Big Heat of a low-desert summer, with its astounding combination of blistering heat and extraordinarily low relative humidity. For both of us, it heralded a new yardstick of what it meant to have hot weather, in ways that would become more and more evident the longer we lived here.

The drive into town also introduced us to the expansive beauty of the Sonoran desert east of town. Sturdy saguaros (Carnegiea gigantea) punctuated the flat ground as far as we could see. Ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens) spread their spiny fingers up and down the hillsides. Glowing chain-fruit cholla (Cylindropuntia fulgida), lacy blue palo verde (Parkinsonia florida), and foothills palo verde (Parkinsonia microphylla) formed a blanket on the land. We were enthralled by so many new plants.

Gary, a man who never met a hill he could resist going to the top of, was nearly delirious thinking of all those crests and ridges and hills. The heat was intense but so was the excitement, and it has hardly dulled since that first day.

We rented a small house to get our bearings and figure out where we wanted to live. Somehow plants began to show up in the backyard almost immediately. We kept them all in pots, because we knew this house was merely a way station, but by the end of the first summer there were over thirty pots out there already. We were giddy with the new-found wonders of this place and with all those exciting new plants. But we had a lot to learn about the growing conditions in our new home.

The air conditioner broke in August, and we were forced to sleep outside on the porch with a fan while we waited for it to be repaired. The repairman turned out to be a fellow plant nut. This man, Lou Steichman, was a dedicated member of the local cactus society, and we would later meet him and his wife through that organization. But on that hot August day he was anonymous, and when he called to me from the roof after noticing all the plants, I was surprised. He knew most of them, and while he worked we compared notes and chatted about care and cultivation. How could I not love a place where the air conditioner repairman was so knowledgeable about plants?

From A Place All Our Own: Lives Entwined in a Desert Garden by Mary F. Irish; ©2012 The Arizona Board of Regents. Reprinted by permission of the University of Arizona Press.