A Desert Communion

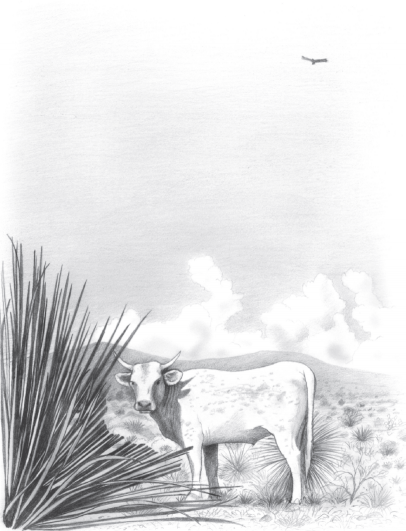

Excerpted from Desert Terroir: Exploring the Unique Flavors and Sundry Places of the Borderlands by Gary Paul Nabhan, Copyright © 2012. Illustrations by Paul Mirocha. Courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

When I was about three years old, I began to see how many lives are engaged in a food chain, in bringing the peculiar tastes of a plant or animal down the earth's cascade of energy on its way to the taster. I would sit underneath a lone peach tree atop a small sand dune that overlooked a tiny, cattail-choked marsh. From that elevated vantage point, I would daydream while watching the birds and insects feed all day long. From dragonflies to jays to woodpeckers, these beings filled my senses as they feasted upon the world.

Late one autumn afternoon, I sat in rapture as I watched two jays bring acorns, other nuts, and even peach pits back to a hollow tree just on the other side of the cattail patch. They would land up in an old cottonwood that had been struck by lightning, and drop acorns down a hollow in the trunk. Soon, a squirrel became alert to their cache, and I could watch him as he crawled down to the base of the cottonwood trunk to steal away with some of the nuts. The jays caught on to his game, and began shrieking, I thought, with laughter. This animated the squirrel enough to make him run up and down the trunk of the tree, which made the jays shriek even louder. As I watched them, I began to find my own acorns in the sand beneath a bur oak, and I piled them on little plates I made with chunks of clay I found beneath the sand.

When the last afternoon light began to fade toward dusk, my mother remembered that I was still back in the sands behind our home. She came out onto the back porch to call me in for my nightly bath.

"What are you still doing out there? You need to come inside – it's nearly dark!!" "Nooo, we're all still gathering acorns for our dinner together!"

"What are you talking about? Get right in here before I give you a little spanking!" She gestured with her hand just like my Lebanese grandpa did when he threatened in Arabic to kick my little butt.

Just then, the two jays flew over me, shrieking at the sight of me having a pile of acorns just like the squirrel had gathered from them. They made such a racket that it stopped my mother in her tracks.

"See, even the jays want me to stay. They're mad at you for wanting to take me away from our feast!"

I may have been putting words into the jays' mouths and anthropomorphizing them a bit, but over the years, I've held fast to my basic tenet: The best feasts and feeding frenzies I've ever participated in were not limited to just one species. They were communions for all creatures.

III

A few years later, I experienced a moment in my life that made me realize that while I could not wholeheartedly embrace the Catholic faith, I could embrace a truly catholic sense of communion and celebration. I had taken my daughter's namesake and godmother, Laura Kerman, back to her desert village down by the border, and I stayed the night on a cot outside her old adobe home. When I awakened just before dawn, my comadre Laura had already fixed me a cup of coffee and was restless to get on with the morning. She asked that I drive her over toward the Catholic churchyard, where a feast day celebration was about to begin.

As I parked my pickup truck and helped the old lady get out of the cab, I could see dozens of her relatives milling around, preparing for the coming of the sun. But it also became clear that they were gathered there for something to eat together. The sun's rays had not yet spilled over the jagged horizon, but two-legged, four-legged, and winged eaters were already present, waiting in anticipation for the Feast of Saint Francis to begin. There were cowboys, farmers, basket weavers, cooks, woodcutters, and water fetchers, along with one young long-haired priest and one old medicine man who wore a huge cowboy hat that came down over his ears.

I watched that medicine man for a while, his face dried and wrinkled and darkened like a desert prune. I realized that his sight was impaired, but I sensed that his vision was still very strong. Not very far behind him, there were horses standing still, dogs milling around, and one restless steer. In the giant cactus closest to this crowd, there were perched a few turkey vultures, some black vultures, and one caracara, the so-called Mexican eagle. From afar, it appeared as though they were huddled together in the embrace of the saguaro's giant arms.

The cowboys mounted their horses and went off to lasso a Corriente steer, to drag him over to the assembly, and to bring him down to the dry, barren ground. It took some doing. When the steer finally fell onto his side and stopped kicking, most of the folks moved in closer. They watched the blind old medicine man turn until he felt the rays of the rising sun warm the side of his face. He turned directly toward the sun to greet it in the east while the young priest sang a song of praise. It was in Latin, and while no one present understood its words, they tried to feel what it meant being sung at dawn. The priest swept his hand in the sign of a cross over the steer's head. The medicine man brushed a branch of pungent creosote bush through a clay bowl of water, lifted it above his head, and whipped the wet branch until it shed its moisture as a blessing, splashing the beleaguered steer. Next, the young priest flicked the hair back from his eyes and sprinkled holy water on the steer as well.

An old bowlegged farmer ambled up to the steer, and as three cowboys held it down, ropes strung tight around them, the farmer cut its throat. Blood spurted onto the ground. The steer quivered and kicked, until enough life had drained out of it that it could rest in peace. One elderly woman watched the whole thing, and then tossed a sprig of creosote bush onto the quieting body; she crossed herself, then walked over to the outdoor kitchen and put on an apron.

Within twenty minutes, the steer's hide had been cut off it like a blanket. Its blood had been drained away. Its entrails and other innards had been heaped up on the hide. Two butchers began to carve off the tenderloins, reduce them to thin strips, and send them over to the fire for immediate grilling. The wizened medicine man and the young long-haired priest were served first, followed by all the women, Laura and the other elderly ladies being brought to the head of the line. They all watched as three young cowboys dragged the hide and its pile of innards some hundred yards or so across the dusty earth, to deposit them just below the giant cactus where the birds remained perched.

As soon as the cowboys dropped the hide and turned their backs to resume the butchering, first the turkey vultures, then the blacks and the lone caracara dropped down to inspect the offering that had been left for them. They hopped about, probing various organs with their beaks, positioning themselves to drag select pieces out of the heap.

As more of the tenderloin strips were being grilled over the glowing coals of mesquite wood – fat dripping into the flames, crackling, sending up a smoky aroma that permeated the air – the scavengers began to eat. They occasionally glanced over to where the butchers still worked, but seemed rather unconcerned about their proximity to the human kind. Meanwhile, the dogs were tossed pieces of fat, or charred pieces of meat too burnt to eat. The dogs watched the people eat, as the people watched the vultures and the caracara.

That evening, I saw them again, circling around us, as more than a thousand Indians, Mexicans, and Anglos assembled for the Feast of Saint Francis at that small desert rancheria. After the Mass, a thousand human mouths tasted the flesh of the same steer that the caracara and vultures had feasted upon. To prepare for the feast over the previous week, no money had been exchanged. One ranching family had agreed to donate the beef more than a year ago. Two families of farmers had gifted their recently harvested beans and chiles and squash. Several woodcutters had brought cords of firewood for the grilling, and for warming the dancers on their occasional breaks between sunset and dawn. Two dozen elderly women diligently grilled the meat, stirred the ingredients into cauldrons of red chile stew, boiled the beans, and fried the squash. Others brewed the coffee, delivered tortillas and cakes, washed dishes and pots, and found plates and cups and dinnerware enough for every person who had arrived. Deer dancers and various musicians – fiddlers, water-drummers, flute players – arrived to perform, but they too did not expect to be paid, other than to partake of the smoke-imbued food with everyone else.

The feast continued on toward dawn. Hardly anyone noticed the coyotes that came in to lick the hide clean of the last of the innards from the carcass. Instead, they all watched as the carved wooden body of Saint Francis was carried around the clearing by four old men, with women and children and dogs following behind them. The light from the campfire glinted off the polished wooden face of the desert saint, making it look as though he was smiling, crying, or filling his eyes full of stars.

Gary Nabhan is an internationally celebrated desert explorer, plant hunter and storyteller with more than four decades of experience foraging, farming, hunting and fishing in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands. He is regarded as a pioneer in the local foods movement. Nabhan is author or editor of 24 books. This book reunites him with Paul Mirocha, the illustrator and co-conspirator of Gathering the Desert, which won the 1986 John Burroughs Medal for best nature writing.