Bringing Back the Bean

My Personal Journey to Reconnect with the Season

It’s fall again, and soon we will be making our way through a new season of farmers’ market fare. As the cooler weather sets in, our favorite winter squash varietals will fill the aisles as the last of the unforgettable summer tomatoes and sweet tastes of local melons bid farewell until next year.

Our desire for different and comforting flavors will present itself in sync with the unfolding new time of year. The foods in front of us are ones we conveniently crave as we ponder their possibilities: artichokes, beets, Medjool dates, sweet potatoes, Swiss chard… Just as in the hotter months, our inherent wisdom will help us to select fruits, vegetables and grains, as well as meats and dairy, that will provide the nutrition, satiety and pleasure we need for the fall.

Or perhaps in our preoccupation with other matters, we have lost the depth of connection between seasons and personal wellbeing. Maybe in our attempt to finely dine or spare some time or dollars, we have dismissed our ability to listen to what we need most, thereby sacrificing our privilege to enjoy. In this, we may have forfeited our freedom to know what our land is doing for us and what we could be doing for it.

The relationship between what the land gives and what we need is deliberate.

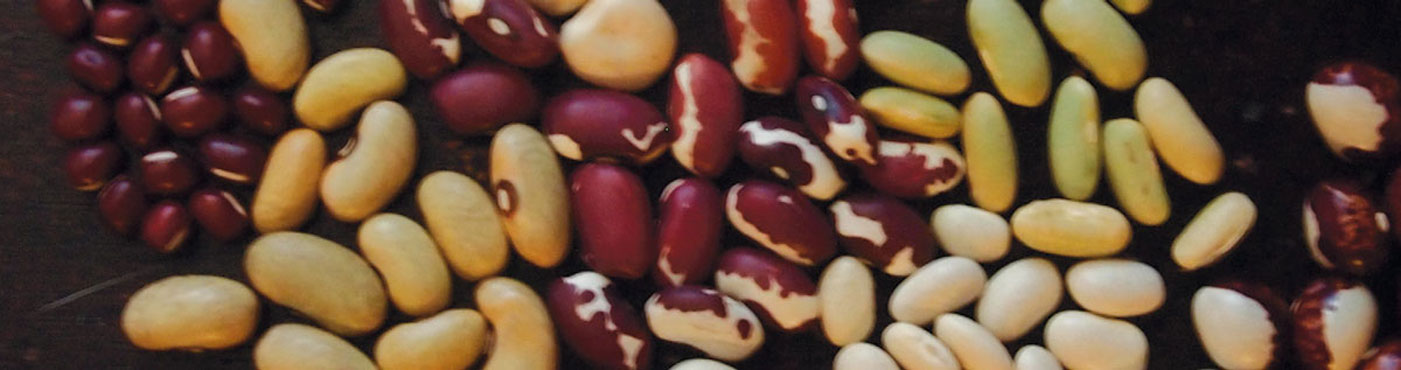

This realization came to me some years ago in the form of a simple bean dish. The chef reminded me through his unpretentious provision of legumes large and small, tomatoes and herbs cooked until tender that I had been cheating myself. Amidst the few ingredients present, the most important elements hit my senses in perfect succession—salt, fat, acid, heat—and were balanced by the sweetness of the tomatoes and the creaminess of the beans.

The meal, one that on my standard American menu might have been considered a side dish, was being served as an entree, and it was apparent why. The chef had recognized the bean’s ability to capture attention, but had also acknowledged this single ingredient’s talent for gratification. It was a large portion, yet I walked away feeling content—not full—and felt a sense of wellness for eating it.

Though the chef did not know it, he had triggered a more soulful, inquisitive reaction in me. I had re-discovered for myself something that has sustained much of the world for centuries. Stopping for a moment, I knew my relationship with the legume had been superficial and that I now wanted to know more about the humble bean. In my naivete, I had enjoyed its ability to satiate but had never given any real thought as to why.

The experience made me reflect on the bean. As a food I frankly have not always felt comfortable with cooking, it was one I had most definitely always loved eating.

The humble seed, even in its simplicity, had been most perplexing to me, a trained culinarian. Canned choices were the most obvious option in the time of cut-corner cuisine and minute meals, but were creatively limiting and generally unappealing. Frozen legumes were equally, if not more, restrictive in selection, and I assumed had less nutritional value after their time spent in multiple cold-cases. Dry beans tortured me. They were my preference, but I didn’t have the patience to soak, rinse, soak and then cook them for long hours. Though beans represented a tasty and nutritional powerhouse, I only bothered with them if someone had done the work for me. I fell into a habit of turning a blind eye, ultimately sacrificing the circularity between land and basic human need.

Realizing that I wasn’t so aloof with other foods, I attempted to delineate what my experience with that bean dish had done for me. How was it possible that I had enjoyed it to such a degree? The taste had trapped me, but what had gripped me? Why would a seemingly simple dish provide such a comforting and pleasing occurrence?

The answers began to become apparent not long after the restaurant experience when I recognized how the quality of the dish seemed to pair so conveniently with the season. I reminded myself of a principle I held high. Alice Waters has said, along with many other chefs for whom I had the utmost respect, “When you have the best and tastiest ingredients, you can cook very simply and the food will be extraordinary.” A pioneer of today’s local food movement, Waters helped to champion ingredient-inspired cooking, allowing the farmers’ markets and seasons, rather than a recipe, to dictate our dishes.

I then began to research organic-legume agriculture, a proactive practice to provide and restore soil’s nitrogen that was used throughout history until after World War II, when synthetic fertilizers became popular in the United States. I found that legumes are nutritional powerhouses for both people and place.

Legumes and cover crops such as alfalfa, clover, kidney beans, soybeans and others provide healthy bacteria that pull nitrogen from the atmosphere, transforming it in the plant’s roots to a type that soil uses to become more fertile. As nitrogen is released, plants in nearby areas benefit. Nutrients are restored to the land, and they ready the soil for another season of planting.

The added benefit of this traditional method is an alternative to the typical, highly processed and often diet-inappropriate animal feeds that also became common in U.S. agriculture after WWII. When legume plants begin to die and are no longer useful to the farmer, animals that are natural grazers such as cattle, horses and chickens can move in and forage, all the while returning a natural fertilizer and helping to till the land. What’s left of the legumes continues to provide nitrogen nutrients, even in its seemingly lifeless form, enforcing a deeper and richer soil that gives back tenfold.

More recently, chefs like New York’s Dan Barber of Stone Barns at Blue Hill or Arizona’s Jeff Kraus of Crepe Bar have taken the concept of cover crops a step further by using them on their menus. Chefs looking to put their creativity to the test, asking their local farmers what unglamorous items they have on hand, can help diversify everyday dietary habits by expanding and redirecting the palate’s pursuit of flavor, which creates a real-time demand for biodiverse foods and conveniently puts dollars directly back into farmers’ hands for crops that might not have had a market.

I concluded that what I had been craving that day at the restaurant were conveniently the things my body also needed. Whether I knew it or not, I had trained myself to love the foods that I required. I’m still not able to explain what I was missing from my diet that the bean dish fulfilled, but I do know that my body’s inherent wisdom had helped me to select something that was essential and beyond mere caloric intake. More so, I drew a connection to the season and the terroir of our desert land. Having immediate access to seasonal, climate-specific foods can satisfy and help us nutritionally so the symbiotic relationship is secured.

Bean or otherwise, taking advantage of what is available to us in each season provides a small peek into a world of possibilities that are programmed to sustain. A kind of synergy perhaps, the formula isn’t so difficult. Just as the seemingly ordinary legume begins its effectual impact with a burst of nitrogen to the soil, we also have an inner ability to make choices that drive change, fittingly fueled by flavor.

An American child raised on Dutch-Indonesian food, Natalie Rachel Morris is now a classically trained culinarian with a masters of arts in food culture and communications. As a W. K. Kellogg Foundation–endowed fellow, she founded the award-winning initiative Good Food Finder and is now the local foods coordinator at Local First Arizona and a professor in the Sustainable Food Systems program at Mesa Community College.