Seed-to-Cup

Coffee, for many of us, is part of our daily routine. Drinking it at our favorite neighborhood coffee shops fosters a feeling of local community, yet coffee is an inherently global product. It is one of those crops that simply will not grow in the Arizona desert.

Specialty coffee requires a very particular tropical climate. In fact, Hawaii and California are the only states in the U.S. that have conditions conducive to coffee farming. Many of the countries that produce our coffee are developing nations with their own complex cultural and political histories. This sets a backdrop to the industry that can be tricky to navigate, both logistically and ideologically.

So, how can we enjoy our cup of joe and feel connected to the people who grew it? Well, it starts with local roasters and coffee shop owners who have made it their mission to directly source their coffee beans. The end goal of seed-to-cup is like farm-to-table: Know, respect and honor your grower, even if they live on the other side of the world.

While a handful of coffee shops in the Valley do their own roasting—and do a notably good job of it—there are fewer that truly have a direct connection to where their unroasted beans are coming from.

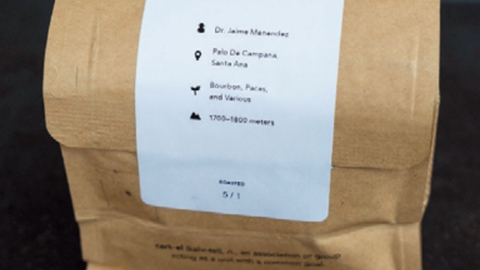

Paul Haworth, the director of coffee production at Cartel Coffee Lab, is one such roaster who prioritizes responsibly and mindfully sourcing the coffees that are served at Cartel. As he has come to know it, direct sourcing does not necessarily mean cutting out the middlemen. On the contrary, coffee is a relational product that travels along a chain; “the goal is to make sure at every step of the way that these are people you trust and are likeminded.”

According to Paul, the beautiful thing about coffee that sets it apart from other specialty products is that it creates a global mosaic of relationships. Because coffee is often grown in nations with strong central government control, there is no way to get around the step-by-step processes required to export it to the U.S. This is not necessarily a bad thing. Rather, coffee trading can encourage meaningful connections when it is sourced responsibly—increasing cultural awareness, educating everyone involved and potentially even enabling positive change on the commodities market where coffee is sold exclusively on price without consideration of the conditions under which it is grown. The fact of the matter is, he says, “Coffee requires many hands and those hands are obviously people and those people have names and they have stories.”

Julia Peixoto Peters of Peixoto Coffee in downtown Chandler knows the stories of many of her growers well, in large part because some also happen to be her family members and former neighbors. Originally hailing from Brazil, Julia is intimately familiar with the industry because she grew up watching her family farm and trade coffee. It was not until several years after moving to Arizona that she realized she wished to carry on her family’s legacy in a tangible way. Her father was the last of his siblings to continue farming coffee so she felt compelled to get involved, though not without reservations. Based on what she saw while growing up, coffee is a risky business with many ups and downs from season to season. Some of those risks include susceptibility to changes in weather, below cost-of-production trade values on the commodities market and unforeseen issues while the coffee is in transit, including theft.

Ultimately, Julia and her husband decided to open a coffee shop because they wanted to have a hand in every step of the process, from the crop on her family’s farm to the coffee in a customer’s cup. She clarifies that she is not the sole buyer of her family’s coffee, nor is her family’s coffee the only coffee served at Peixoto. They work to responsibly source all of their coffees and to know the stories behind them. As well, they distribute Peixoto coffee to other businesses that appreciate their family’s story, including the sustainability and transparency that comes with it. “We’ve always wanted to open the doors, not only for my family but for farmers in our region to sell direct to as many people as possible.”

Having seen it firsthand, Julia emphasizes the importance of not only knowing where your coffee comes from, but how much the farmers who grew it are paid. Because it is an agricultural product, there are many hands that touch it and lives that depend on it. While some may think Julia gets a sweetheart deal when purchasing her family’s coffee, it is quite the opposite. She actually pays more than most other buyers, she says, because she wants to “make sure that the money is where all the work is, where all the risks are—where it belongs.” On average, Peixoto pays $1-$3 more per pound. When coffee is trading at around $1 per pound, that is a two- to fourfold increase of the farmers’ incomes.

Similarly, Paul says buying coffee for Cartel at anything but well above cost-of-production is out of the question. Anything less translates to impossibly low or nonexistent profit margins for growers, and therefore wages for workers. Couple that with the technical difficulty of growing a product that is consistent year to year and the coffee industry is riddled with uncertainty.

For many years, the Peixoto family’s coffee was sold on the commodity market, so they never knew who was buying their coffee. It was going from middleman to middleman, broker to roaster somewhere across the world, without much personal connection along the way. They were just business transactions. Now, Julia’s family can work directly with her and a few exporters who they trust. Her father, José Augusto, even visited the shop in Chandler to see the end product of his work on the farm. It was one of the first times he got to taste the coffee made from his beans and see other people enjoying it too. “People approach him like he’s a celebrity,” she laughs.

Both Paul and Julia agree that relationships with growers need to be a two-way street and there is a need for improvement in the way coffee is traded. By investing in relationships rather than chasing after the best quality coffee that can be bought at the cheapest price, they can show producers what is marketable and help them understand how to reinvest resources in ways that benefit the quality of their crop. “We feed that information back because farmers can learn and apply the processes that will bring the beverage that the consumers want,” says Julia. This better serves the direction that the specialty coffee market is trying to evolve in—one that is transparent, equitable and sustainable.

So why aren’t all specialty coffee roasters focused on relational sourcing? Paul and Julia will tell you, it is not always straightforward. Some countries do not have the infrastructure to support a transparent trade market. Further, roasters must dedicate themselves to asking the hard questions of their importers, including how much the farmers are being paid relative to the cost of the beans. This detailed information is not always readily available and requires some digging. It takes time, effort and a high level of commitment from small local businesses.

Lawrence Jarvey, co-owner of Provision Coffee, can certainly attest to this fact. “I think the biggest thing about seed-to-cup for me is that it’s beyond the industry and definition, it’s really a way of life for us.”

As an independent roaster, Lawrence wants to know the people that Provision is directly affecting, both consumers and producers. One such connection is with Ben Carlson of Long Miles Coffee. Ben and his American family live in Burundi and oversee the operation of their own coffee bean washing station. In doing so, they directly control not only quality, but also how much their farmers are paid. While not an everyday part of the coffee trading that takes place between Lawrence and Ben, Provision has even gone so far as to purchase cattle for the community that helps grow their coffee in Burundi. It was their hope that this would provide both manure for their growers and milk for the locals.

“By definition, Provision means to provide things like shelter, water, health, education. So, we’re working with nonprofits on the ground who also directly affect that market. We’ve worked really, really hard on creating those strong relationships in certain places in the world; we think people should really know that it’s not easy.”

Not easy, but undoubtedly worthwhile. As such, the small local coffee shops who do their due diligence—buying goodquality coffee, treating it with respect and marketing it appropriately—see themselves as a collective rather than competition. Lawrence says, “I hope that more shops fall in alignment, if not with farmers directly, then with brokers who are being conscious. Conscious of how they are buying and who they are buying from, and how they are impacting communities — not just trying to buy really rare, scarce, high-scoring coffees.” He believes that a shift in the way people think about products like coffee could have a big impact, changing the world even beyond the coffee industry.

Changing the world sounds like a lofty goal, but sometimes the world is smaller than we think. Lawrence tells the story of his very first coffee purchase, which came after he had a vision for Provision as a company and told someone he wanted to learn more about coffee. His friend said he had met a man on a plane a few years back who grew coffee as part of a cooperative in Guatemala. By the miracle of the internet, Lawrence was able to track the farmer down on Facebook. He told the man he was interested in buying his coffee, to which he replied, ‘Yeah, I don’t know if you’re the right guy.’ A six-month dialogue and a visit to the farm in Guatemala followed. The farmers wanted to make sure that Lawrence was ready to embark on a journey alongside their team, not just buy coffee for one season. Lawrence still works with those farmers seven years later.

Our local coffee purveyors will be the first to tell you that such stories of genuine direct sourcing are still very much the exception, not the rule. Many coffee shop owners and employees can tell you the différence between washed or natural, fruity or chocolatey, acidic or not-so-acidic taste profiles. The challenge is to find the ones who can tell you about passionate and fairly compensated growers, mindful importers and attentive roasters, too. They will also tell you that you are an integral part of the story. For Cartel Coffee Lab, Peixoto Coffee and Provision Coffee, it is not only about seed-to-cup but also community-to-community.

Lawrence, Julia and Paul each laughingly say they can talk anyone’s ear off about their coffee if they let them. So chat them up the next time you stop in for your caffeine fix. You will leave with an even greater appreciation for the local purveyors who truly care about their customers, what ends up in their coffee cups and the communities that make it all possible, near and far. Inside their shops, they do more than pour cups of coffee; they pour their heart and soul into building the communities around them.