Real Cowgirls Eat Sheep

Maurrie Sussman is so much more than just the founder of Sisters on the fly, the national women’s fishing and vintage travel trailer adventure club; she’s also a sort of substitute mom to a large family living on the Navajo Nation. It was entirely natural then that Maurrie would seek to cross-pollinate her two passions—the adventuring Sisters on the fly cowgirls and her Navajo “family,” the Chees. They came together for a weekend this past May, when the cowgirls immersed themselves into the life of the Native American family, right down to the traditional sheep slaughter.

In Tonolea, about halfway between Tuba City and Kayenta in the heart of the Arizona plateau, the visit of 17 women and their trailers was looked upon as a cause for celebration and, of course, a traditional sheep slaughter. A sheep-centered feast is the focal point of any Navajo (Diné) family gathering, whether it is a graduation, a wedding or a return from military duty, and the arrival of Maurrie and the Sisters was no exception.

Keith Chee, the family’s che (the Navajo word for grandfather; not to be confused with the family’s surname, Chee), welcomed the women and the rain that they (in his mind) had brought. He offered a blessing that was really gratitude for the water that would ensure that this year’s maize crop—which he lovingly plants himself—would get off to a good start. Speaking only the guttural Athapaskan of his tribe, Che is an 84-yearsyoung gentle man who still practices the traditions of his people. Even upon first meeting, he exudes wisdom, strength and an incredible sense of peace.

His granddaughter, a 21-year old-bilingual certified nursing assistant at the hospital in Page, was Che’s primary translator as she is at work. She’s unusual, as the younger set predominantly speaks English. The Chee family admits that across the tribe the old language, and with it the culture, is becoming less and less prevalent with each generation, due in no small part to the pressures of the often basic lifestyle and the call of nearby Western development.

All the family members were at the Chee family home to welcome the cowgirls and to participate in the sheep slaughter. Although seemingly a big job, through the family’s devotion and division of labor the slaughter would be accomplished with efficiency, precision and reverence for this integral arc in the circle of life. Not a drop of blood, a tuft of wool nor a moment of time would be wasted.

In general, a 2- to 3-year-old sheep is preferred for its size and maturity. From the family’s 21-member flock (12 being lambs), the selection was made based upon “a feel of the tail,” which seeks just the right amount of fat deposits that are the tell-tale sign of optimal flavor. Interestingly, one of the two black sheep was chosen for the celebration. The color, Che’s son-in-law Riggley assured the ladies, had no significance.

The fore and hind legs of the freshly shorn black sheep were bound to one another with a strip of fabric, and it rested peacefully beneath a roughly hewn two-sided shed. The shed featured a crossbeam from which an empty rope dangled. The only “tools” in sight were a series of ancient-looking wood-handled knives of varying blade sizes arrayed on a wooden bench alongside the shed wall.

Che selected the largest knife and gently knelt behind the sheep’s head, cradling it in his arm with an expression of love and gratitude for the gift the animal was about to provide. He swiftly cut the throat while his 14-year-old grandson Ricky caught the blood in a pink basin held beneath the incision. Once full, the bowl was spirited away to the nearby house for later use in blood sausage.

With countenances of sincere reverence, several people made quick work of skinning the animal, working the knife blade between the wool-laced skin and the muscle with deft motions. Others (including the Sisters who work as ICU nurses) assisted as the knife wielders swiftly carved out a solid piece of hide from the entire animal. The pelt was spread on the ground, wool side down, and used as a clean place for laying the knives and the organ meats as they emerged. The dangling rope then took up its duty and was used to hold the body by the back legs to facilitate dismantling the carcass into useable components.

As sweet rain pelted the onlookers, another large bowl appeared as a catchment for emptying the abdomen. The bowl was also removed to the house, where Che’s daughter Aurelia took up her station to clean the contents. Outside, her husband Raymond continued butchering under the roof of the shed. Section by section he broke down the parts, finally coming to the bladder, which was removed with a swift cut and run promptly over to the dirt where it was punctured so as not to contact the hanging meat. Next, the well-sheltered heart and coveted liver were carefully pulled from their lairs deep inside.

Meanwhile, Tasha worked beside her sister Aurelia, cutting the quarters into chops and other useable portions, and cleaning what gourmands refer to as the offal. In current culinary literature, eating offal is often extolled as the pinnacle of gastronomy: One who recognizes the true character of the parts otherwise cast off has climbed to the peak of taste. Unlike the houses of haute gourmet, there in the shadow of Wildcat Peak, on land with no running water or electricity, it was more a matter of not wasting a single part.

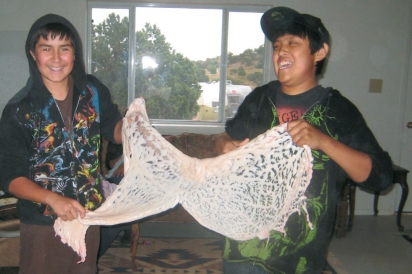

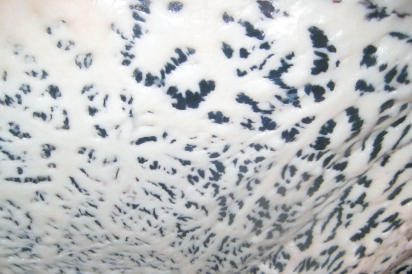

Aurelia extruded the large and small intestines, carefully rinsing them with clean water, inside and out. The stomach was taken outside and its contents returned to the earth. Che’s teen grandsons Ricky and Joseph waved around the fat layer that had been carefully separated from the abdomen. The single three-foot by two-foot rectangle’s opaque construction was reminiscent of the patterns of lace or delicate snowflakes. The boys were actually stretching it out to dry as they moved it to the pure outdoor air.

While the propane grill was ignited and warming, the men lit a wood fire. When the coals were white-hot, the homemade grate (itself a work of art featuring horseshoe handles at either end and a body formed of heavy wire knitted into a pattern of half-inch squares) was placed on the fire to cradle strings of intestine wrapped in the abdomen fat, which sizzled alongside the liver. Aurelia and her sister Tonya hand-molded tortillas from a bowl of dough and browned then in the spaces between the meats.

While we gathered for the meal, a tray was passed containing the savory bits of grilled fat-wrapped intestine. The cowgirls immediately began comparing the taste to bacon, which spawned a discussion of the white man’s name for the delicacy—Navajo Rumaki, anyone?

Meanwhile, chunks of fatted leg meat grilled on the stainless steel four-burner barbecue. The meat met its destiny folded into warm, puffy Blue Bird flour tortillas topped with chunks of boiled carrot and potato, wrapped in foil and served as a mutton sandwich. (Blue Bird flour is milled in Cortez, Colorado, and available exclusively in Indian country.) Although a bit stringy and tough to the bite, the sheep meat shredded easily and yielded a fresh, hearty and rich flavor.

That evening was not the last of the sheep. The following night, the Sisters completed a thousand rotations of the Navajo “skip dance” to the chanting of a quartet of aged men and a single hand drum, while dressed in the flowing skirts and velvet shirts that are the formal wear of celebratory Navajo woman and holding hands with members of the extended Chee family. The hungry revelers were in for a dish called hominy stew that captured the essence of our hosts’ way of life. It was a huge pot of simmering, falling-off-the-bone tender sheep back and leg portions floating in a deep, exquisitely flavored broth alongside kernels of Che’s dried corn that had regained only part of their moisture, yielding a bit of a bite.

The soup was so captivating that the Sisters and the family returned for seconds, shunning the fry bread which is usually a favorite. Many sucked the bones as they savored every last morsel of meat that clung to them.

Just three ingredients—sheep, corn and, the most precious of all, water—came together to create a luscious and hearty one-pot meal. The dish changed the energies of the earth into the flavors of love and created the fuel for living; a beautifully simple testament to a basic, yet rich culture that revels in the very blessing of life.